Review Article

Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis in Adults. A Systematic Review

Diego Abelardo Alvarez Hernández1,2*, Alberto Manuel González Chávez3,4 and Alexia S Rivera1

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad Anáhuac México Norte, Mexico State, Mexico

2Coordination of Medical Services, Cruz Roja Mexicana I.A.P Delegación Huixquilucan, Mexico State, Mexico

3Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad Panamericana, Mexico City, Mexico

4Department of General Surgery, Hospital Español de México, Mexico City, Mexico

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Diego Abelardo Álvarez Hernández, Coordination of Medical Services, Mexican Red Cross PAR Huixquilucan Office, Mexico, Tel: 52+1+5539996092; Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 04 April 2017; Approved: 24 April 2017; Published: 26 April 2017

How to cite this article: Alvarez Hernández DA, Chávez AG, Rivera AS. Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis in Adults. A Systematic Review. Heighpubs Otolaryngol and Rhinol. 2017; 1: 020-031.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.hor.1001005

Copyright License: © 2017 Alvarez Hernández DA, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Adults; Facial; Necrotizing fasciitis

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Necrotizing Fasciitis (NF) is a rapidly progressing, severe suppurative infection of the superficial fascia and the sorrounding tissues that may lead to necrosis, septic shock and death if left untreated. Facial NF is rarely seen and symptoms may be non-specific at the onset and depend on the origin site and the stage of the disease, making it difficult for diagnosis.

Materials and Methods: A systematic review was done following the PRISMA guidance. PubMed database was searched for case reports published between January 2007 and March 2017. Full text articles were obtained and assesed for relevance. Data extraction was performed as an iterative process.

Results: A total of 24 articles, describing 29 adult patients with facial NF were included. Facial NF was more common in males. Skin trauma was the most frequent mechanism of lesion and diabetes mellitus was the most common associated systemic disorder. Periorbital area was the most affected area. In order of appereance, swelling and pain were the most common initial clinical manifestations. Group A Streptococcus was the most frequent microorganism isolated. Advanced airway management was needed in more than 50% of the cases and surgical management was done in 90% of the cases.

Conclusions: Practitioners should be aware of its existance, epidemiology, etiology, risk factors and initial clinical manifestations to develop a high index of suspicion, to order studies that may discard or confirm the diagnosis, and to offer prompt treatment to preserve patient’s life and reduce the disfigurement and disability that it may cause.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a rare, progressive and potentially fatal soft tissue infection characterized by widespread necrosis of the fascial planes and the surrounding tissues [1]. Hippocrates was the first to give a specific description of NF, but the first modern account of NF was done by Jones in 1871 and the term NF was first used by Wilson until 1952 [2]. Overall incidence is estimated in 3.5 cases per 100,000 persons [3], with a mortality rate between 10% to 40% and can figure as high as 80% without an early medical or surgical intervention [4]. NF frequently involves the extremities, abdominal wall and perineum, but cervico-facial involvement is extremely rare [1]. As in any infection, the disease involves a precipitating event, an infectious agent and a host, being an odontogenic infection the most common precipitating event and Group A Streptococcus the most common infectious agent [3]. Pathogenesis is characterized by bacteria invasion of subcutaneous tissues, rapid horizontal spread of infection along the deep fascial planes and release of bacterial toxins, which results in tissue ischemia and liquefactive necrosis [5]. The abscence of specific symptoms can cause that practitioners miss in the diagnosis at the beginning of the disease and if left untreated, it can rapidly lead to septic shock and death. Once suspected, management should consist of immediate resuscitation according to patient’s needs, administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and early surgical intervention [6]. The objective of this systematic review was to collect and analyze data regarding demographics, epidemiology, etiology, mechanisms of lesion, associated systemic disorders, initial clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of facial NF cases reported through the last decade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic review was done following the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) guidance. The PubMed database was searched using the search terms “Necrotizing fasciitis” [Mesh], “facial”and “adult”. The search was limited to case reports written in English and published between January 2007 and March 2017. Abstracts were screened and full text articles were obtained and assessed for relevance by authors. Articles were excluded if they reviewed pediatric cases, if their main focus was other different than NF, if they reviewed NF on other body sites, if they were unable to be localized or if they didn’t reported enough information about patients. Data extraction was performed as an iterative process and Microsoft Excel program was used for basic stadistical analysis.

RESULTS

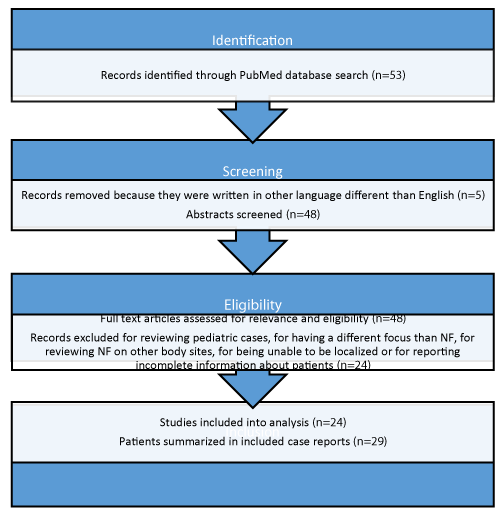

A total of 53 articles were obtained during the initial search. From the 53 articles, 5 were published in other language different than English, and therefore, were excluded. A total of 48 full text articles were obtained and assessed for eligibility. From the 48 articles, 24 were excluded because 1 article focused on pediatric cases, 18 articles had a different focus than NF and just mentioned it as an underlying disease or presented incomplete information about patients, 2 articles reviewed NF on other body sites and 3 articles were unable to be localized. A total of 24 articles, describing 29 adult patients with facial NF were included. Most studies presented one case report, meanwhile one study presented two case reports and two studies presented three case reports. The full systemic review search process is shown at figure 1 and detailed patient data is supplied at table 1.

| Table 1: Parameters of the cases included in the Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis systematic review. | |||||||||||

| Reference | Year | Sex | Age | Mechanism of lesion | Associated systemic disorders | Localization | Initial clinical manifestations | Initial antimicrobial treatment | Microorganisms isolated in cultures | Other antimicrobial treatments | Death |

| Eltayeb et al. [7] | 2016 | Female | 19 | Skin trauma | None present | Lower lip, chin and submental area | Skin lesion, pain, swelling and fever | Penicillin | None isolated | Ceftriaxone, Gentamycin and Metronidazole | No |

| Ormenisan et al. [8] | 2015 | Male | 52 | Radiation | Chronic alcohol abuse and squamous cell carcinoma | Right maseterin and latero-cervical areas | Odontogenic pain and swelling | Amoxicilin | Not performed | Ceftriaxone, Gentamycin and Metronidazole | No |

| Choi et al. [9] | 2014 | Female | 32 | Skin trauma | None present | Chin | Skin lesion, pain, swelling and purulent discharge | Ampicillin-Sulbactam | S. liquefaciens complex and S. intermedius | Ceftriaxone | No |

| Casey et al. [10] | 2014 | Male | 46 | None present | None present | Left upper eyelid | Pain, swelling and erythema | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | Group A Streptococcus | Clindamycin | No |

| Nagamoto et al. [11] | 2014 | Male | 28 | Odontogenic infection | Hemophagocytic syndrome and chemotherapy | Right side of the face | Swelling and dispnea | Itraconazole | P. aeruginosa and P. lilacinus | Amphotericin B, Micafungin and Voriconazole | No |

| Lee et al. [12] | 2014 | Female | 61 | None present | Diabetes mellitus and hepatitis C | Right infraorbital area and the cheek | Pain, swelling and fever | Not specified | Not mentioned | Does not apply | Yes |

| Richir et al. [13] | 2013 | Female | 43 | Skin trauma | None present | Left periorbital area | Skin lesion, edema, pain, swelling, blushing and fever | Not specified | Group A Streptococcus | Does not apply | No |

| Bucak et al. [14] | 2013 | Female | 36 | None present | None present | Submental and submandibular area | Pain, swelling, dysphagia, common status failure, poor level of nourishment and fever | Imipenem | S. viridans | Does not apply | No |

| Bucak et al. [14] | 2013 | Male | 81 | None present | None present | Left temporal area and common neck region | Pain, swelling, asymmetric appearance, toothache, dysphagia, common status failure, poor level of nourishment and fever | Imipenem | None isolated | Does not apply | Yes |

| Bucak et al. [14] | 2013 | Female | 40 | Odontogenic infection | None present | Submental and right submandibular area | Pain, swelling, toothache, dysphagia, common status failure, poor level of nourishment and fever | Not specified | Prevotella spp | Meropenem | No |

| Ulu et al. [6] | 2012 | Male | 50 | Odontogenic process | None present | Right submandibular area | Pain, swelling, dyspnea, hoarseness, dysphagia and fever | Cristallized Penicillin and Clindamycin | Not mentioned | Does not apply | Yes |

| Ulu et al. [6] | 2012 | Female | 51 | None present | Diabetes mellitus | Submental and submandibular area | Pain, swelling, dysphagia and fever | Meropenem | Not mentioned | Does not apply | No |

| Yadav et al. [15] | 2012 | Male | 63 | Odontogenic infection | Diabetes mellitus | Left submandibular area | Pain, swelling, erythema, trismus and dysphagia | Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid and Metronidazole | Streptococcus spp and S. aureus | Does not apply | No |

| Murray et al. [16] | 2012 | Female | 33 | Multisystemic trauma | None present | Left malar and periorbital area | Fever, discoloration and numbness | Not specified | Not mentioned | Not specified | Yes |

| Park et al. [17] | 2011 | Female | 36 | Odontogenic infection | Bell palsy | Left mandibular area | Pain and swelling | Erythromycin | S. anginosus and Bacteroides | Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Ceftriaxone, Clindamycin, Metronidazole Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Vancomycin | No |

| Bilodeau et al. [18] | 2011 | Male | 59 | Skin trauma | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and pituitary adenoma | Periorbital and glabellar area | Pain, edema and erythema | Bacitracin and Cephalexin | Group A Streptococcus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus | Ceftriaxone, Clindamycin, Penicillin, Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Vancomycin | No |

| Bilodeau et al. [18] | 2011 | Male | 57 | Odontogenic infection | Chronic alcohol abuse, smoking and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Right mandibular area | Lethargy, weakness, pain and swelling | Penicillin V Potassium | P. buccae | Ampicillin-Sulbactam and Clindamycin | No |

| Bilodeau et al. [18] | 2011 | Male | 57 | None present | Obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease and congestive heart failure | Right temporal area through the clavicles | Pain and swelling | Penicillin | S. viridans, E. corrodens, Peptostreptococcus and E. coli | Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Vancomycin and Metronidazole | No |

| Lee et al. [19] | 2011 | Male | 51 | Skin trauma | Smoking, diabetes mellitus and hypertension | Upper lip | Pain, swelling, erythema, purulent discharge and fever | Cephalexin | Corynebacterium, E. cloacae and group D Streptococcus | Amoxicillin-Clavulanic Acid and Gentamycin | No |

| Medeiros et al. [20] | 2011 | Male | 37 | Odontogenic infection | Chronic alcohol abuse | Facial, cervical and thoracic area | Pain and trismus | Ceftriaxone and Metronidazole | K. pneumoniae | Does not apply | No |

| Gürdal et al. [1] | 2010 | Male | 33 | Blunt trauma | None present | Forehead and right periorbital area | Pain, swelling and edema | Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid | Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 3rd generation Cephalosporin, Crystallized Penicillin and Metronidazole | No |

| Lim et al. [21] | 2010 | Female | 22 | None present | Congenital bilateral dysplastic kidneys, renal failure, renal transplant, diabetes mellitus and chemotherapy | Left upper eyelid | Swelling, erythema, purulent discharge and fever | Ampicillin and Cloxacillin | P. aeuroginosa | Ciprofloxacin, Clindamycin, Erythromycin and Meropenem, | Yes |

| Pepe et al. [22] | 2009 | Female | 74 | None present | Diabetes mellitus and hypertension | Right cheek and cervical area | Not mentioned | 3rd generation Cephalosporin | C. tropicalis, C. albicans, S. epidermidis, S. capitis spp Ureolyticus and E. cloacae | Amikacin, Amphotericin B, Cefotaxime, Ciprofloxacin, Gentamycin, Meropenem, Metronidazol, Piperacillin and Vancomycin | No |

| Rath et al. [23] | 2009 | Male | 55 | None present | None present | Upper face | Swelling, edema and fever | Cefoperazone, Linezolid and Sulbactam | Candida spp and A. flavus | Fluconazole | No |

| Aakalu et al. [24] | 2009 | Male | 42 | Skin trauma | Chronic alcohol abuse | Right periorbital area | Pain, swelling, erythema and dema | Aztreonam, Clindamycin, Levofloxacin and Vancomycin | Group A Streptococcus | Does not apply | No |

| Bilbault et al. [25] | 2008 | Male | 44 | Odontogenic process | Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Right malar area | Pain, swelling and erythema | Cefotaxim, Gentamycin and Metronidazole | E. coli, S. epidermidis and Propiobacterium | Does not apply | No |

| Akcay et al. [26] | 2008 | Female | 78 | None present | None present | Eyelids and left cheek | Pain, swelling and erythema | 3rd generation Cephalosporin | None isolated | Ampicillin-Sulbactam and Fluoroquinolone | No |

| Hohlweg et al. [27] | 2007 | Male | 53 | Skin trauma | None present | Periorbital area | Pain, swelling and erythema | Cephalosporin | Group A Streptococcus | Clindamycin and Penicillin G | No |

| Raja et al. [28] | 2007 | Male | 19 | Skin trauma | None present | Right lower eyelid | Pain, swelling and erythema | Benzyl Penicillin, Cefuroxime and Clindamycin | None isolated | Amphotericin, Ethambutol, Isoniazid and Rifampicin | No |

ANALYSIS OF THE RESULTS

Sex and age: From the total of 29 cases, 17 (59%) were males and 12 (41%) were females. The mean age was 46.62 years with a standard deviation of 15.66.

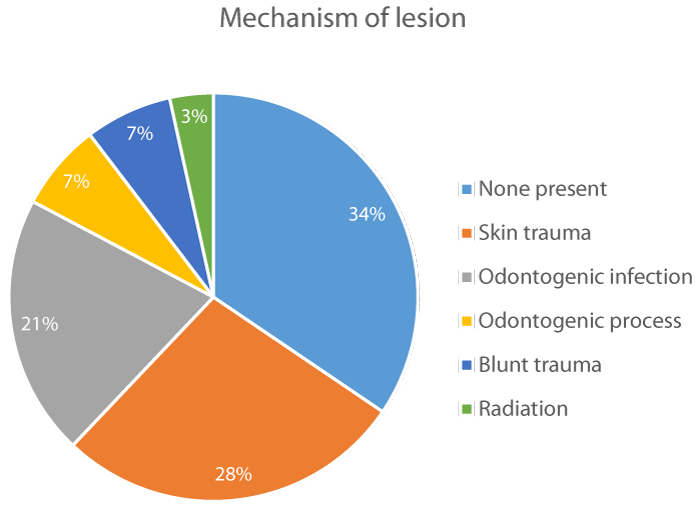

Mechanism of lesion: Skin trauma was the most common mechanism of lesion that we observed, as it was reported in 8 cases (28%). It was followed by odontogenic infection in 6 cases (21%), odontogenic process in 2 cases (7%) and blunt trauma and radiation in 1 case (3%). None mechanism of lesion could be identified in 9 cases (31%) figure 2.

Associated systemic disorders: Cases analyzed were assessed in search of patients comorbidites. Six patients presented one associated systemic disorder and 9 patients presented more than one. None associated systemic disorders were reported in 14 patients. In order of frequency, the most common associated systemic disorders were diabetes mellitus (8 cases), hypertension (4 cases), chronic alcohol abuse (3 cases) and smoking and chemotherapy (2 cases), followed by hyperlipidemia, hepatitis C, squamous cell carcinoma, hemophagocytic syndrome, pituitary adenoma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, congenital bilateral displasia of the kidneys, renal failure, renal transplant and Bell palsy (1 case).

Localization: Reported data indicated that 14 patients had only one affected area by the disease and that 15 patients had more than one. Facial NF was most commonly found in the periorbital area, followed by cervical region, eyelids, submandibular area, temporal area, cheeks, submental area, malar and mandibular areas, lips, forehead, glabellar area, chin and thoracic region.

Initial clinical manifestations: The most common signs and symptoms were swelling and fever, with 25 and 24 patients reporting them as their initial clinical manifestations, respectively. Fever was reported by 12 patients, eyrthema by 10, dysphagia by 6, edema by 5 and purulent discharge, common status failure and poor level of nurishment by 3. The complete list of initial clinical manifestations with the number of patients reporting them and their percentages is shown at table 2.

| Table 2: Initial clinical manifestations of the Facial Necrotazing Fasciitis reported cases. | ||

| Initial clinical manifestations | Number of patients | Percentage of appearance |

| Swelling | 25 | 86% |

| Pain | 24 | 83% |

| Fever | 12 | 41% |

| Erythema | 10 | 34% |

| Dysphagia | 6 | 21% |

| Edema | 5 | 17% |

| Toothache | 3 | 10% |

| Purulent discharge | 3 | 10% |

| Common status failure | 3 | 10% |

| Poor level of nurishment | 3 | 10% |

| Trismus | 2 | 7% |

| Dyspnea | 2 | 7% |

| Skin lesion | 2 | 7% |

| Discoloration | 1 | 3% |

| Hoarseness | 1 | 3% |

| Lethargy | 1 | 3% |

| Weakness | 1 | 3% |

| Numbness | 1 | 3% |

| Assymetric appearance | 1 | 3% |

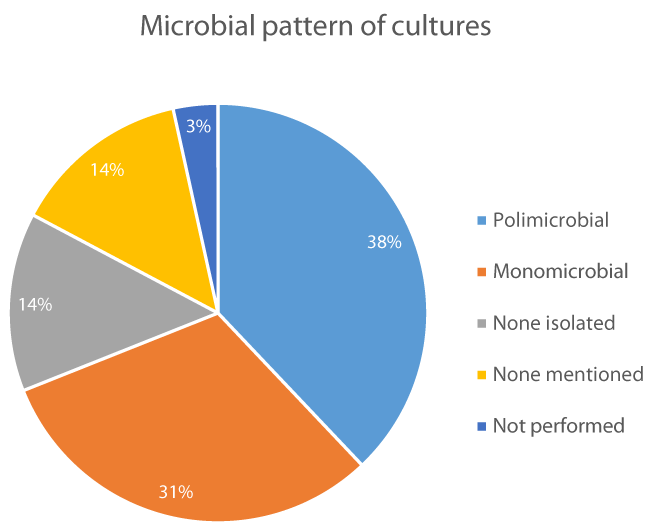

Diagnosis: Data regarding laboratory and imaging studies from the analyzed cases was extracted. Laboratory values were mentioned or reported in 21 cases (72%), but most of them were incomplete or just referred and in 8 cases (28%) they weren’t mentioned at all. Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score could not be assessed because of those reasons. Bacterial culture was done in 24 cases (83%), it wasn’t mentioned in 4 cases (14%) and it wasn’t performed in 1 case (3%). When culture was done, a monomicrobial pattern appeared in 9 cases (31%), menwhile a polimicrobial pattern appeared in 11 cases (38%). None microorganism could be isolated in 4 cases (14%) and none microorganism was specified in other 4 cases (14%) figure 3. The most common microorganisms isolated in order of frequency were; Group A Streptococcus (5 cases), Candida spp (3 cases), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus viridans, Prevotella spp and Enterobacter cloacae (2 cases), Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus intermedius, Staphylococcus capitis spp Ureolyticus, Group D Streptococcus, Group F Streptococcus, Streptococcus spp, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides, Corynebacterium, Propiobacterium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Eikenela corrodens, Serratia liquefaciens complex, Paecilomyces lilacinus and Aspergillus flavus (1 case).

To confirm the diagnosis of facial NF, the initial imaging method used was the Computarized Tomograpy (CT) scan in 19 cases (65%), meanwhile the combination of Radiography to rule out other differential diagnosis and CT scan to confirm the facial NF diagnosis was used in 2 cases (7%). None imaging method was mentioned in 8 cases (28%).

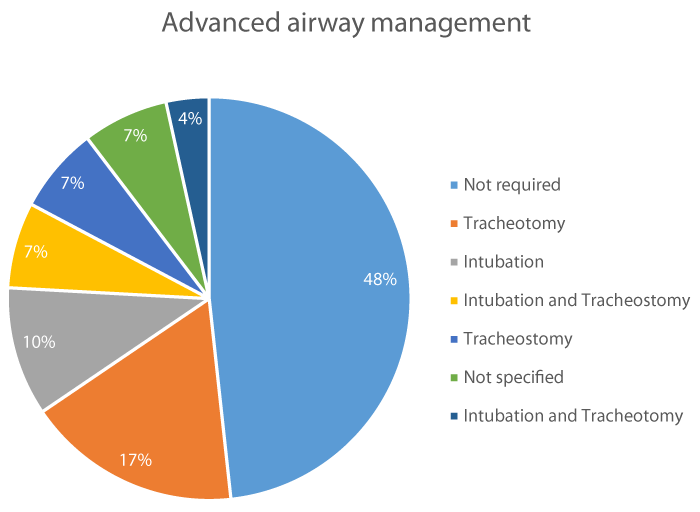

Management and treatment: Advanced airway management was required in 15 cases (52%); 5 required tracheotomy (17%), 3 intubation (10%), 2 intubation and tracheostomy (7%), 2 tracheostomy (7%) and 1 intubation and tracheotomy (3%). In 2 cases the advance airway management wasn’t specified (7%) figure 4. The initial antimicrobial treatment was specified in 25 cases (86%) and from the total of 29 cases, antimicrobial treatment was adjusted in 19 cases (16%) once that the antimicrobial susceptibility test results were obtained or when treatment failure seemed to appear.

Finally, debridement was done in 26 of the cases (90%) and death due to the appereance of complications occurred in 5 cases (17%).

DISCUSSION

The systematic review that we made provides valuable information about facial NF cases in adults that have been published through the last 10 years. It demonstrates how their trends and behaviours have been through the last decade and coincides with the information published from previous series. It also shows the need of a standard form for reporting clinical cases, as there is great variability among the content of the cases that we analyzed, making it difficult to assess some parameters and impossible to assess others.

NF is a rapidly progressing, severe suppurative infection of the superficial fascia, often associated with vascular thrombosis and necrosis of the overlying skin [29]. NF can be classified in 2 types: Type I is a polimicrobial infection caused by anaerobic and aerobic bacteria, which occurs most commonly after surgical procedures in patients which present some comorbidities. Common isolates in this group include; Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus spp, Enterococcus, Escherichia coli, Peptostreptococcus spp, Prevotella and Porphyromonas spp, Bacteroides fragilis and Clostridium spp. Type II is a monomicrobial infection which occurs in healthy patients. Its most commonly caused by group A Streptococcus, but methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus has also been described in this type of infection [3]. Furthermore, yeast-like fungi causing fasciitis in inmunocompromised patients has also been reported [4]. Our systematic review showed by a slight proportion that most of the analyzed cases corresponded to NF type I. However, group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes) was the most commonly found microorganism. We also found case reports caused by a yeast-like fungi infection in inmunocompetent patients, which rules out the previous thoughts about the need of being inmunocompromised to develop this kind of infection. Currently, as the number of microorganisms that cause NF seems to continue ascending, epidemiologic surveillance is one of the areas which urges to be reinforced.

NF is commonly observed in the extremities, abdominal wall and perineum. Facial and cervical NF are rarely seen [15]. Within the face, the infection spreads along the superficial musculo-aponeurotic system, a fascial plane that is contiguous with the muscles of facial expression and stretches from the frontalis muscle to the platysma. Extensive necrosis of the fascia and surrounding subcutaneous tissues ensues providing a nourishing culture medium for bacterial growth [17]. Furthermore, odontogenic infections can spread through the sublingual and submandibular regions and parapharyngeal spaces to the base of the skull, neck, mediastinum and chest [22]. The number of case reports that we found about facial NF in the last 10 years demonstrates its rareness if compared with other body sites. Our results showed that the most common site of facial NF was the periorbital area, as other authors have mentioned before. However, we had trouble in trying to specify other facial areas where the infection began, as several case reports didn’t provided specific details about it.

In the majority of NF cases involving the face, a trauma history is reported, but in the NF cases involving the neck, the disease tends to follow an odontogenic or oropharyngeal infection [15,30]. Advanced age, blunt or penetrating trauma, burns, chronic alcohol abuse, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus infection, intravenous drug abuse, malnutrition, obesity, organ failure, peripherial vascular disease, severe liver disease and patients with underlying malignancy are prone to acquire this type of infection. These risk factors define the induction, progression and results of the disease, as several of them produce leukocyte disfunction, reduced chemotaxis, phagocytosis and opsonization. Futhermore, hyperglicemia, the hallmark of diabetes mellitus, suppress the immune system and enhances bacterial growth [6,15,19,31]. Respect to risk factors, trauma history and odontogenic infection represented the 63% of the mechanisms of lesion reported in our review, in accordance with what has been written in the literature. However, 34% of the cases didn’t had any known risk factor at all; Just one of the analyzed cases corresponded to a patient of advanced age (≥65 years), demonstrating that facial NF can develop at all ages (we focused our review on adult patients, but there is available an excellent pediatric review conducted by Zundel et al. [5]); Diabetes mellitus was the most frequent associated disorder and as the global epidemics of this disease continue to rise, more cases of NF should be expected; Chronic alcohol abuse and smoking were other risk factors present at some cases and they can be modified, therefore, practitioners should encourage patients to leave these habits for their own good.

Symptoms of NF may be nonspecific at onset and depend on its origin site and the stage of the disease, leading to misdiagnosis. The infection typically begins with an area of erythema that quickly spreads within the course of hours to days. The erythema spreads rapidly and the margins of infection can move out into normal skin without being raised or sharply demarcated. As the disease progresses, the skin will turn dusky or purplish at the site of the infection. Multiple identical patches can develop to produce a large area of gangrenous skin as the infection speads. The most important signs are tissue necrosis, bullae, putrid discharge, gas production, rapid spread through the fascial planes and the abscence of the classic tissue inflamatory signs. A positive “finger test” result is characterized by a lack of resistance to finger dissection in normally adherent tissues. Systemic findings can include fever, tachycardia and hypotension [6]. The main clinical finding, especially at the onset of the disease, is pain, which is sudden and violent [14]. The extreme and disproportionate sensation that it cause seems to be pathognomonic and it is likely caused due to neural involvement [32]. Then, facial swelling follows quickly. Fever occurs within a few hours but it can be delayed. Other symptoms like dyspnea, dysphagia, trismus and otalgia are less usual [14]. From the 29 analyzed cases included in our review, the most common initial clinical manifestations reported were swelling and pain, followed by fever and erythema. Theses signs and symptoms are commonly found in several pathologies and because of this, practitioners, specially Otorrinolaryngologysts who frequently receive patients with facial and cervical symptomatology, should be aware of considering facial NF in their differential diagnosis when a patient refer having sudden and violent pain, as they may play an important role in the health care system chain. Leukocytosis, anemia, hypocalcemia and acidosis can be expected to occur and are caused by the direct effects of bacterial toxins, as well as by consequent organ failure [22]. The main complications of facial NF are airway obstruction, vascular thrombosis, mediastinitis and septic shock [33].

Because delay in diagnosis and treatment may result in death or in the destruction of facial tissue, leading to unsightly disfigurement or functional deficits, it is important to recognize the entity early and treat aggressively and thoroughly [34]. Laboratory values can also aid in the diagnosis of NF. Useful laboratory tests include complete blood count, an electrolyte panel, a coagulation profile, blood and tissue cultures, urinalysis and arterial blood gases. They are useful because values can be assigned to the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score in order to assess the likelyhood of having NF; serum C-reactive protein >150 mg/L (4 points), white blood count >25 x103/µL (2 points) and between 15 to 25 x103/µL (1 point), hemoglobin <11 g/dL (2 points) and between 11 to 13.5 g/dL (1 point), serum creatine >1.6 mg/dl (2 points) and serum glucose >180 g/dL (1 point). A score <5 indicates a probability of less than 50% of having NF, meanwhile a score >6 should raise the suspicion of having NF at 75 to 80% [16]. Several analyzed cases reported or mentioned laboratory results, but not all of them reported their values and they weren’t standarized. Therefore, we could not assess the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis score. Authors should take this in consideration, as it is an important data for practitioners who read their cases that help them to better understand the inner changes of patients who suffer from NF. The case report of Pepe et al. [22] should be taken as an example, as they report in an organized table several laboratory values from different days.

Imaging techniques play an important role in assessing the full extent of the disease and give insights on treatment planning [22]. Soft tissue radiography, CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are most useful when gas is present, but often they show only soft tissue swelling [16]. The gold standard for diagnosis is intravenous contrast CT scan which can distinguish between abscesses, erisipelas or cellulitis, allows to make a better description of the characteristics of the lesions and can give a hint on monitoring of the disease, recurrence of the purulence and new gas formation [6,35]. We observed that in almost 2/3 of the cases the gold standard was performed, but probably the numbers would rise if we could manage to obtain more information from the cases who didn’t mentioned them at all. Imaging techniques continue to be excellent aid tools for confirming NF diagnosis, but they shouldn’t pose a delay on treatment if inconclusive.

Supportive therapy, intravenous wide-spectrum antibiotics and surgical intervention are the most accepted treatment modalities for the successful management of NF; [15] Airway management requires special attention as complications can be life-threatening [6]. Patients should be resuscitated according to his/her clinical state and evidence of hemodynamic instability demands intensive care support with immediate resuscitation through hydroelectrolitic reposition. Also, nutritional support is required from the first day of the patient’s admission to the hospital in order to replace lost fluids and proteins from large wounds. Metabolic demands are similar to those of other major trauma or burns, which means that the patient need twice the basic caloric requirements; [37] Broad-spectrum antibiotics such as aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, clindamycin, metronidazole and penicillins should be instituted early and adjusted by subsequent Gram stain, speciation and antimicrobial sensitivity tests are performed. Aggressive debridement is pivotal in achieving a successful outcome. However, this presents a quandry when the infection is localized at the face. Surgeons are often conservative in the debridement of facial tissue due to the fear of disfigurement, but a conservative approach in facial NF is frequently not curative and necessitates multiple reoperations. A surgeon performing debridement in facial NF must thus maintain a careful balance between excising an adequate amount of tissue and taking caution to spare important structures such as the facial nerve to minimize disfigurement [17]. Other adjunctive approaches to treatment that still are controversial due to a wide range of results obtained, include hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) therapy and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG); The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) does not recommend HBO therapy because it has not been proven as a benefit to the patient and may delay resuscitation and surgical debridement; Respect to IVIG, the IDSA recommends its use in Group A Streptococcus infection [25]. Finally, more than half of the reported cases that we analyzed requiered advanced airway management, remarking the importance of protecting the patient’s airway as swelling may develop in a life-threating region. The initial antibiotic treatment provided in most cases was consistent with what the guidelines propose, however, the incresead antimicrobial resistance continues to pose a challenge for practitioners as several antimicrobials are becoming obsolet. Antimicrobial treatment should be adjusted once that results from cultures and the antimicrobial susceptibility tests are obtained in order to enhance the patient’s clinic response and improve their outcomes. Mortality rate was of 17%, between the expected range.

CONCLUSION

Even if facial NF is extremely rare, practitioners should be aware of its existance, etiology, epidemiology, risk factors and initial clinical manifestations to develop a high index of suspicion, and therefore, to order laboratory and imaging studies that may discard or confirm the diagnosis, to offer prompt and adequate treatment, including ABC management with speciall emphasis on airway conditions, intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical intervention to preserve patient’s life and reduce the stigma that it may cause. Otorinolaryngologysts have a great area of opportunity to detect this kind of patients and should work in alliance with a multidisciplinary team including anesthesiologists, surgeons and infectologists to improve the health system response.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. María José Díaz Huízar for her technical support.

REFERENCES

- Gurdal C, Bilkan H, Sarac O, Seven E, Yenidunya MO, et al. Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis Caused by Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis. Orbit. 2010; 29: 348-350. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1OQJx4

- Ord R, Coletti D. Cervico-facial necrotizing fasciitis. Oral Dis. 2009; 15: 133-141. Ref.: https://goo.gl/u3cWYR

- O’Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, Lynfield R, Gershman K, et al. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential implications: United States, 2000 -2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45: 853-862. Ref.: https://goo.gl/uHU6cY

- Dhaif G, Al-Saati A, Bassim M, Cabs A. Management Dilemma of cervicofacial Necrotizing fasciitis. J Bahrain Med Soc. 2009; 21: 223-227.

- Zundel S, Lemarechal A, Kaiser P, Szavay P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2017; 27: 127-137. Ref.: https://goo.gl/WRxtOC

- Ulu S, Ulu SM, Oz G, Kacar, Emre, et al. Paralysis of cranial nerve and striking prognosis of cervical necrotizing fasciitis. J Craniofac Surg. 2012; 23: 1812-1814. Ref.: https://goo.gl/olQZpt

- Eltayeb AS, Ahmad AG, Elbeshir EI. A case of labio-facial necrotizing fasciitis complicating acne. BMC Res Notes. 2016; 9: 232. Ref.: https://goo.gl/fkzT1m

- Ormenisan A, Morariu SH, Cotoi OS, Vartolomei MD, Grigoraş RI, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis in oro-maxillo-facial area after radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the soft palate. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015; 56: 847-850. Ref.: https://goo.gl/YOmnux

- Choi HJ. Cervical Necrotizing Fasciitis Resulting in Acupuncture and Herbal Injection for Submental Lipoplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 2014; 25: 507-509. Ref.: https://goo.gl/u6cAYN

- Casey K, Cudjoe P, Green III JM, Valerio IL. A Recent Case of Periorbital Necrotizing Fasciitis-Presentation of Definitive Reconstruction Within an In-Theater Combat Hospital Setting. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014; 72: 1320-1324. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LbgDjy

- Nagamoto E, Fujisawa A, Yoshino Y, Yoshitsugu K, Odo M, et al. A Case of Paecilomyces lilacinus Infection Occuring in Necrotizing Fasciitis-associated Skin Ulcers on the Face and Surrounding a Tracheotomy Stoma. Med Mycol J. 2014; 55: 21-27. Ref.: https://goo.gl/OG4cim

- Lee JH, Choi HC, Kim C, Sohn JH, Kim HC. Fulminant Cerebral Infraction of Anterior and Posterior Cerebral Circulation after Ascending Type of Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014; 23: 173-175. Ref.: https://goo.gl/x1jNNz

- Richir MC, Schreurs HH. Facial Necrotizing Fasciitis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013; 14: 428-429. Ref.: https://goo.gl/A74QPt

- Bucak A, Ulu S, Kokulu S, Oz G, Solak O, et al. Facial paralysis and mediastinitis due to odontogenic infection and poor prognosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2013; 24: 1953-1956. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7NZowG

- Yadav S, Verma A, Sachdeva A. Facial necrotizing fasciitis from an odontogenic infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012; 113: 1-4. Ref.: https://goo.gl/5FkFtw

- Murray M, Dean J, Finn R. Cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis and steroids: case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012; 70: 340-344. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7nRwrf

- Park E, Hirsch EM, Steinberg JP, Olsson AB. Ascending necrotizing fasciitis of the face following odontogenic infection. J Craniofac Surg. 2012; 23: 211-214. Ref.: https://goo.gl/YsK688

- Bilodeau E, Parashar VP, Yeung A, Potluri A. Acute cervicofacial necrotizing fasciitis: Three clinical cases and a review of the current literatura. Gen Dent. 2011; 60: 70-74. Ref.: https://goo.gl/3VuJiZ

- Lee JT, Hsiao HT, Tzeng SG. Facial necrotizing fasciitis secondary to accidental bite of the upper lip. J Emerg Med. 2011; 41: 5-8. Ref.: https://goo.gl/MVZsU2

- Medeiros Junior R, Melo-Ada R, Oliveira HF, Cardoso SM, Lago CA. Cervical-thoracic facial necrotizing fasciitis of odontogenic origin. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011; 77: 805. Ref.: https://goo.gl/o6B38l

- Lim VS, Amrith S. Necrotising fasciitis of the eyelid with toxic shock due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Singapore Med J. 2010; 51: 51-53. Ref.: https://goo.gl/FDNScm

- Pepe I, Lo-Russo L, Cannone V, Giammanco A, Sorrentino F, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the face: a life-threatening condition. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009; 21: 358-362. Ref.: https://goo.gl/AMmVoX

- Rath S, Kar S, Sahu SK, Sharma S. Fungal periorbital necrotizing fasciitis in an immunocompetent adult. Opthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 25: 334-335. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ih1ooO

- Aakalu VK, Sajja K, Cook JL, Amjad ZA. Group A Streptococcal Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Eyelids and Face Managed With Debridement and Adjunctive Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Opthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009; 25: 332-334. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ANflF9

- Bilbault P, Castelain V, Schenck-Dhif M, Schneider F, Charpiot A. Life-threatening cervical necrotizing fasciitis after a common dental extraction. Am J Emerg Med. 2008; 26: 5-7. Ref.: https://goo.gl/9dgCoV

- Akcay EK, Cagil N, Ylek F, Anayol MA, Cetin H, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of eyelid secondary to parotitis. Eur J Opthalmol. 2008; 18: 128-130. Ref.: https://goo.gl/0kAiYl

- Hohlweg-Majert B. Necrotizing fasciitis. Opthalmology. 2007; 114: 1422. Ref.: https://goo.gl/eLvfKs

- Raja V, Job R, Hubbard A, Moriarty B. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis: delay in diagnosis results in loss of lower eyelid. Int Ophtalmol. 2008; 28: 67-69. Ref.: https://goo.gl/xDswXw

- Meleney FL. Hemolytic Streptococcus gangrene. Arch Surg 1924; 9: 317-364. Ref.: https://goo.gl/XzYijD

- Flynn TR, Shanti RM, Levi MH, Adamo AK, Kraut RA, et al. Severe odontogenic infection, part 1: prospective report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64: 1093-1103. Ref.: https://goo.gl/SrGAWu

- Bono G, Argo A, Zerbo S, Valentina T, Procaccianti P. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis and descending necrotizing mediastinitis in a patient affected by neglected peritonsillar abscess: a case of medical negligence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008; 15: 391-394. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UdGRP2

- Seal DV. Necrotizing fasciitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2001; 14: 127-132. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jVL4gE

- Wang LF, Kuo WR, Tsai SM, Huang KJ. Characterizations of life-threatening deep cervical space infection: a review of one hundred ninety-six cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003; 24: 111-117. Ref.: https://goo.gl/uf64wA

- Lee TC, Carrick MM, Scott BG, Hodges JC, Pham HQ. Incidence and clinical characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus necrotizing fasciitis in a large urban hospital. Am J Surg. 2007; 194: 809-812. Ref.: https://goo.gl/0KtR5X

- Santos-Gorjón P, Blanco-Pérez P, Morales-Martín AC, del Pozo de Diosb JC, Estévez Alonsob S, et al. Deep neck infection. Review of 286 cases. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2012; 63: 31-41. Ref.: https://goo.gl/lp8X2n

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dale Everett E, Dellinger P, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2014; 59: 10-52. Ref.: https://goo.gl/t5CGYi

- Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, Sotiropoulos D, Kanavidis P, et al. Current Concepts in the Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014; 1: 36. Ref.: https://goo.gl/eulv5a